Why is it important to understand The Nixon Shock now?

Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff reminds us that history rhymes in the latest edition of Foreign Affairs Magazine

Pretend you’re in charge of US monetary and fiscal policy—somehow you are both Fed Chairman and Treasury Secretary—how would you deal with massive government debt, rising budget deficits, eroding confidence in the dollar, record trade deficits, and great power competition?

2025 is not the first time the US has faced that question. And how it gets answered today will have implications for generations, just as it did last time.

In August 1971—with the dollar under the pressure from gold outflows and concerns about an economic slowdown—Nixon installed Arthur Burns as Fed Chairman and worked with Treasury Secretary John Connally to shut the gold window, apply price & wage freezes, and impose a 10% tariff on imports (listen to the series).

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

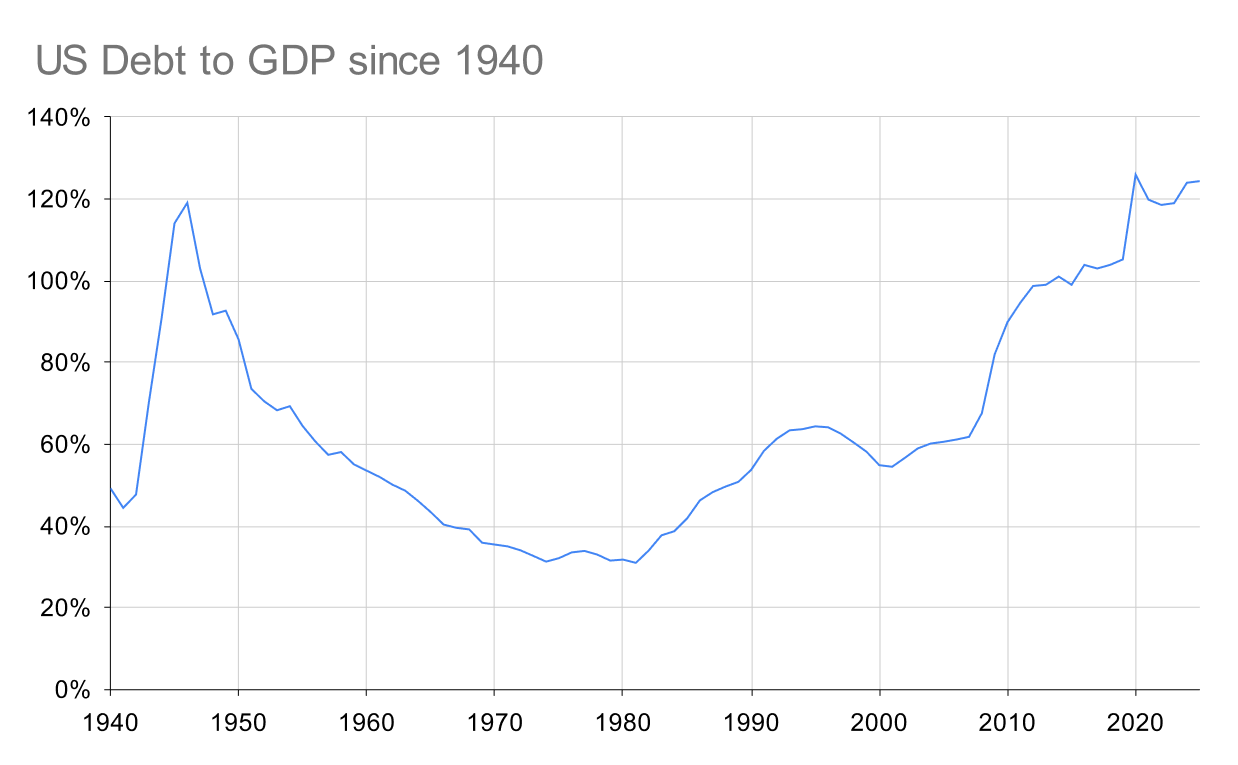

Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff makes the case in the latest edition of Foreign Affairs that, “with long-term interest rates up sharply, public debt nearing its post–World War II peak, foreign investors becoming more skittish, and politicians showing little appetite for reining in fresh borrowing, the possibility of a once-in-a-century U.S. debt crisis no longer seems far-fetched.” (Issue: Sept/Oct 2025)

How might this play out? Could the US attempt to unilaterally restructure the global monetary system again?

“Already, the Trump administration has hinted at more drastic actions to deal with mounting debt payments, should gaining control of the Fed not be enough. The so-called Mar-a-Lago Accord, a strategy put forward in November 2024 by Stephen Miran, now head of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers [and one of the leading candidates to replace Jay Powell as Fed Chairman], suggests that the United States could selectively default on its payments to the foreign central banks and treasuries that hold trillions of U.S. dollars.” (Issue: Sept/Oct 2025)

The US doesn’t have to stop paying interest to default. It can simply print more dollars, thus inflating its currency to reduce the real value of its outstanding debt. This would be like paying my mortgage with the leaves I raked from my yard rather than the money in my bank account—as if money literally grew on trees. Of course, when the US does it, the effect is often to increase the price of goods and services across the economy.

If we want to prepare ourselves, our portfolios, our companies—we need to learn from history. We need to look back in time to understand how this played out in similar times.

How can we tell if we’re headed for a global monetary restructuring, or a major debt crisis?

How do money, assets, and people behave during one of these?

How would it affect geopolitics?

It’s hard to predict the future, and close to impossible to time markets. But it’s not hard to prepare—by studying history.